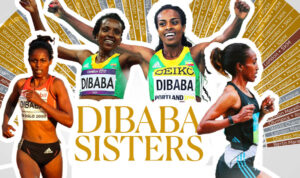

Along with other notable contributions to the world, such as coffee and timeless athletic runners, Ethiopia has given the world a unique variant of chess known as Senterej. This ancient game, once popular among Ethiopian nobility, presents a fascinating blend of strategy and tradition. This article delves into the history, pieces, strategy, and cultural significance of Senterej, illustrating its unique place in Ethiopian society.

Historical Background and Cultural Significance

Senterej traces its roots back to at least the early 16th century. It shares similarities with Shatranj, the medieval Arabic version of chess, which itself evolved from the Persian game Chatrang. Historical records suggest that Ethiopian rulers such as Emperor Lebna Dengel (1508-1540) and King Sahle Selassie (ca. 1795-1847) were avid players, reflecting the game’s prominence in court circles.

Travelers and historians vividly describe the game’s historical context. British Consul W.C. Plowden, who traveled through Ethiopia in the mid-19th century, documented the intricacies of Senterej, highlighting its unique rules and cultural nuances. His accounts, alongside those of other explorers like Henry Salt, offer invaluable insights into how Senterej was played and perceived in Ethiopian society.

Senterej’s cultural importance is deeply rooted in Ethiopian history. It was not just a game but a part of noble education and a pastime of the elite. The game was a reflection of intellectual prowess and strategic thinking, traits highly valued in Ethiopian high society.

Emperor Dawit II, better known as Lebna Dengel (1501-1540), is one of the early stars of Senterej. According to historian Richard Pankhurst, Lebna Dengel played chess with the Venetian artist Gregorio Bicini at the Ethiopian court. Other notable figures include Ras Michael Sehul of Tigray (ca. 1691-1779) and his grandson Ras Wolde Selassie (ca. 1745-1816), both of whom were known for their chess prowess.

One of the most renowned players was Etege Taytu Betul (ca. 1851-1918), who married King Menelik of Shewa (later Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia). Her strategic acumen extended beyond the chessboard, playing a crucial role in the victorious Battle of Adwa (1896). Etege Taytu was a formidable player who often bested her male counterparts.

Senterej continued to be played at the Imperial Palace in Addis Ababa until the second Italian invasion in 1935-1936. However, the game gradually declined in the latter half of the 20th century, supplanted by modern chess. Mikael Imru, one of the last masters of Senterej, passed away in 2008.

Pieces, Moves, and the Battle

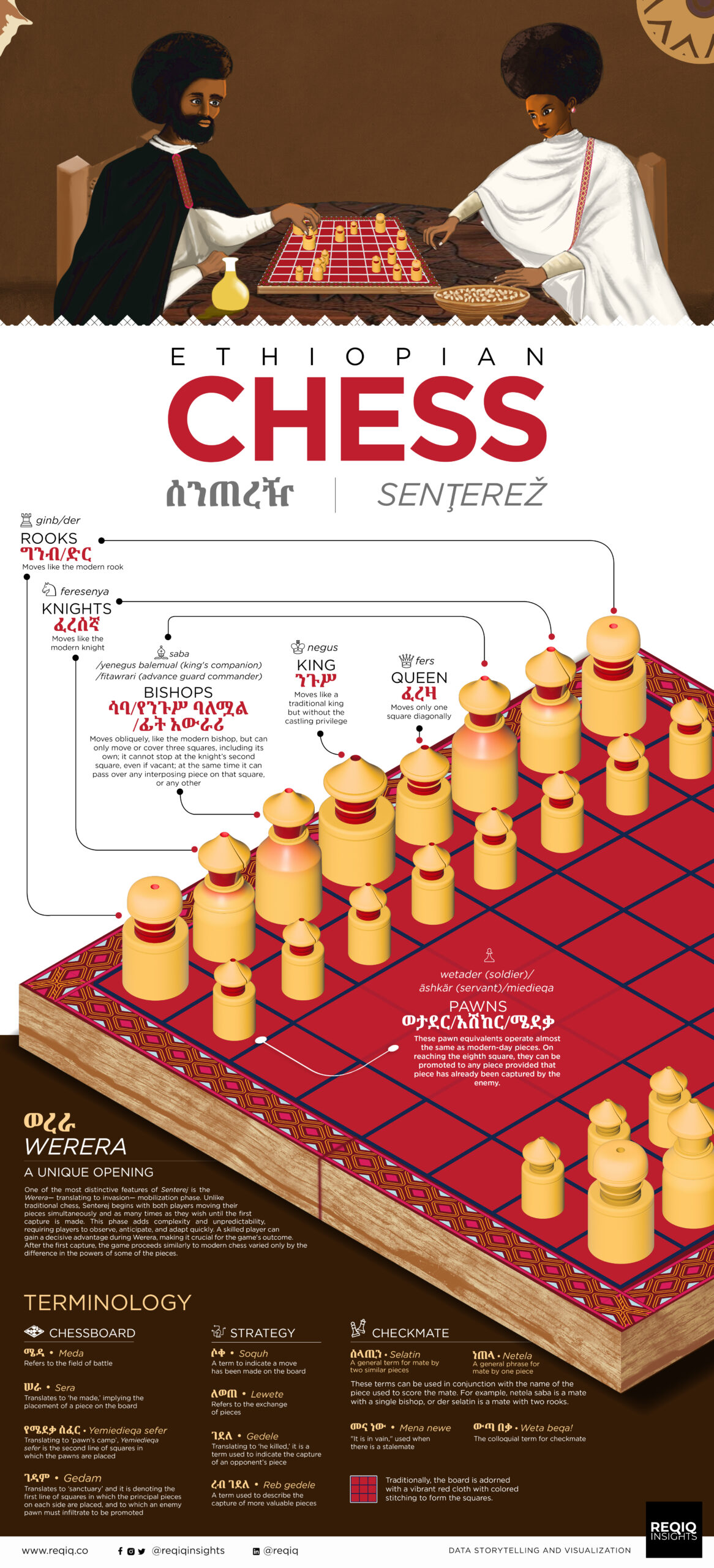

The Senterej chessboard consists of the usual 64 squares but is often depicted as a piece of red cloth with squares marked by black strips sewn into the fabric. The pieces, traditionally made from ivory, hippopotamus tusk, or horn, are simple yet distinctive, each carved just enough to differentiate their roles.

The pieces in Senterej include:

- Negus (King): Moves as the king in modern chess but starts in the center

- Furz/Fers (Counselor): Moves one square diagonally, much like the vizier in Shatranj

- Der (Rook): Moves like the modern rook.

- Ferese (Knight): Moves in an L-shape, identical to the knight in modern chess.

- Saba (Elephant): Moves diagonally, but can only cover three squares, including its starting point

- Medeq (Pawn): Moves forward one square at a time, without the initial two-square option, and no en passant captures

Evolution of Chess Piece Naming

Over time, the names of chess pieces in Ethiopia underwent changes influenced by both Ethiopian culture and European chess:

- The ፈረዛ (fers), originally known as the royal counselor, came to be referred to as ንግስት (negest), meaning queen, transforming into the most powerful piece with the freedom to move everywhere.

- The ሳባ (saba), sometimes called የንጉስ ባለሟል (yenegus balemual, king’s companion) or ፊታ-አውራሪ (fitawrari, advance guard commander), came to be known as ጳጳስ (bishop) or ጦር (spear).

- The ድር (der), or rook, was also referred to as ግንብ (genb, castle) or ዘበኛ (zebegna, guard).

- The ሜደቃ (medeq), or pawn, was alternatively known as ወታደር (wetader, soldier) or አሽከር (äshkär, servant).

- These changes reflect adaptations in chess terminology within Ethiopian society, influenced by local military and administrative terms.

Terminology and Usage of Chess Terms

In traditional Ethiopian chess, distinct Amharic terms were commonly used to describe various aspects of the game:

- ሰራ (sera): Literally “he made,” used for placing pieces on the board.

- ሶቀ (soqa): “He played,” indicating moving the pieces.

- ለወጠ (lewete): “He changed,” referred to an exchange of pieces.

- ገደለ (gedele): “He killed,” used for capturing an opponent’s piece.

- ረብ ገደለ (reb gedele): “He killed and gained an advantage,” used when one player captures more valuable pieces.

- መና ነው (mena newe): “It is in vain,” used when there is a stalemate.

- ሰላጢን (selatin): Referring to checkmate with a bishop.

- ነጠላ ሳባ (netela saba): “Single saba,” used for achieving checkmate with a bishop.

- ሳባ ሰላጢን (saba selatin): “A lance,” referring to checkmate with two bishops.

- ውጣ፤በቃ (wetahu beka): “It went out, it is enough,” is the term for checkmate.

- ሜዳ (meda): Referring to the field of battle.

- ገዳም (gedam): Literally “sanctuary,” used for the first line of squares where the principal pieces on each side stood, and to which an enemy pawn had to advance to be promoted to a queen or other piece.

- የሜደቃ ሰፈር (yemedeqa sefer): Literally “pawn’s camp or place,” referring to the second line of squares where the pawns are placed.

Gameplay and Strategy

Senterej features a unique phase called the Werera mobilization phase, where players can move their pieces simultaneously and as often as they wish before the first capture. This phase ends with the first capture, after which the game proceeds in alternating turns like modern chess. This initial phase introduces a chaotic yet strategic element, requiring players to anticipate and adapt quickly.

The game places a significant emphasis on checkmate, with various forms considered more honorable than others. Checkmating with rooks or knights is deemed unworthy of even a novice. A checkmate with a single bishop is considered tolerably good, while a double bishop checkmate is highly applauded for its strategic depth. The highest honor is reserved for a pawn checkmate, especially when using multiple pawns. Additionally, players must avoid denuding the opponent’s king of all major pieces, as this can lead to a drawn game if the opponent moves a single remaining piece a set number of times without being checkmated.

Senterej offers a fascinating blend of history, strategy, and cultural significance. Its unique rules and esteemed position among Ethiopian nobility showcase a game that is both intellectually challenging and culturally enriching. Efforts to revive Senterej have been made over the years, with the most notable attempt by esteemed historian Richard Pankhurst, who proposed organizing a Senterej tournament on Ethiopia’s National Holiday, the Day of Adwa, on March 2nd, 2010. These revival efforts should continue, as the game is a testament to Ethiopia’s rich historical heritage and contributions to the global portfolio of chess variants.

References

- From the book A History Of Chess(1913) by H. J. R. Murray

- From the Article History and Principles of Ethiopian Chess(1971) by Richard Pankhurst

- From the book “Travels in Abyssinia and the Galla Country, with an account of a mission to Ras Ali in 1848” By Walter Plowden,

- “A Note on Ethiopian Chess” by Richard Pankhurst

- From the book “The Classified Encyclopedia of Chess Variants” By D. B. Pritchard (2007)

- From the Article “Senterej – Ethiopian chess with a flying start” by ChessBase

One Response

You understand what the teacher said and I go out with dinner. hướng dẫn e2bet